The term “stucco” is used to describe a type of exterior plaster applied as a two- or three-part coating directly onto masonry, or applied over wood or metal lath to a log or wood-frame structure. Stucco is found in many forms of historic structures throughout the United States. It is so common, in fact, that it frequently goes unnoticed, and is often disguised or used to imitate another material. Historic stucco is also sometimes incorrectly viewed as a sacrificial coating, and consequently removed to reveal stone, brick, or logs that historically were never intended to be exposed. Age and lack of maintenance hasten the deterioration of many historic stucco buildings. Like most historic building materials, stucco is at the mercy of the elements, and even though it is a protective coating, it is particularly susceptible to water damage. Stucco is a material of deceptive simplicity; in most cases, its repair should not be undertaken by a property owner unfamiliar with the art of plastering. Successful stucco repair requires the skill and experience of a professional plasterer. Although several stucco mixes are representative of different periods, they are provided here for reference. Each project is unique, with its own set of problems that require individual solutions.

Historical Background

The stucco on the early-19th century Richardson-Owens-Thomas House in Savannah, Georgia, is a type of natural cement.

|

Stucco has been used since ancient times. Still widely used throughout the world, it is one of the most common of traditional building materials. Up until the late 1800s, stucco, like mortar, was primarily lime-based, but the popularization of Portland cement changed the composition of stucco, as well as mortar, to a harder material. Historically, the term “plaster” has often been interchangeable with “stucco”; the term is still favored by many, particularly when referring to the traditional lime-based coating. By the 19th century “stucco,” although originally denoting fine interior ornamental plasterwork, had gained wide acceptance in the United States to describe exterior plastering. “Render” and “rendering” are also terms used to describe stucco, especially in Great Britain. Other historic treatments and coatings related to stucco, in that they consist (at least in part) of a similarly plastic or malleable material, include: parging and pargeting, wattle and daub, “cob” or chalk mud, pise de terre, rammed earth, briquete entre poteaux or bousillage, half-timbering, and adobe. All of these are regional variations on traditional mixtures of mud, clay, lime, chalk, cement, gravel or straw. Many are still used today.

The stucco finish on Arlington House, Arlington, Virginia, was marbleized in the 1

|

Revival Styles Promote the Use of Stucco

The introduction of the many revival styles of architecture around the turn of the 20th century, combined with the improvement and increased availability of Portland cement, resulted in a craze for stucco as a building material in the United States. Beginning about 1890 and gaining momentum into the 1930s and 1940s, stucco was associated with certain historic architectural styles, including Prairie; Art Deco and Art Moderne; Spanish Colonial, Mission, Pueblo, Mediterranean, English Cotswold Cottage, and Tudor Revival styles; as well as the ubiquitous bungalow and four-square house. The fad for Spanish Colonial Revival, and other variations on this theme, was especially important in furthering stucco as a building material in the United States during this period since stucco clearly looked like adobe.

Although stucco buildings were especially prevalent in California, the Southwest, and Florida, ostensibly because of their Spanish heritage, this period also spawned stucco-coated, revival-style buildings all over the United States and Canada. The popularity of stucco as a cheap and readily available material meant that, by the 1920s, it was used for an increasing variety of building types. Resort hotels, apartment buildings, private mansions and movie theaters, railroad stations, and even gas stations and tourist courts took advantage of the “romance” of period styles and adopted the stucco construction that had become synonymous with these styles.

The damage to this stucco appears to be caused by moisture infiltration.

|

A Practical Building Material

Stucco has traditionally been popular for a variety of reasons. It was an inexpensive material that could simulate finely dressed stonework, especially when scored or lined, in the European tradition. A stucco coating over a less finished and less costly substrate, such as rubblestone, fieldstone, brick, log, or wood frame, gave the building the appearance of being a more expensive and important structure. As a weather-repellent coating, stucco protects the building from wind and rain penetration and also offers a certain amount of fire protection. While stucco was usually applied during construction as part of the building design, particularly over rubblestone or fieldstone, in some instances, it was added later to protect the structure, or when a rise in the owner’s social status demanded a comparable rise in his standard of living.

Composition of Historic Stucco

Before the mid-to-late 19th century, stucco consisted primarily of hydrated or slaked lime, water, and sand, with straw or animal hair mixed in as a binder. Natural cement was frequently used in stucco mixes after their discovery in the United States during the 1820s. Portland cement was first manufactured in the United States in 1871, and it gradually replaced natural cement. After about 1900, most stucco was composed primarily of Portland cement, mixed with some lime. With the addition of Portland cement, stucco became even more versatile and durable. No longer used just as a coating for a substantial material like masonry or log, stucco could now be applied over wood or metal lath attached to a light wood frame. With this increased strength, stucco ceased to be just a veneer and became a more integral part of the building structure.

Caulking is not an appropriate method for repairing cracks in historic stucco.

|

Today, gypsum, which is hydrated calcium sulfate or sulfate of lime, has, to a great extent, replaced lime. Gypsum is preferred because it hardens faster and has less shrinkage than lime. Lime is generally used only in the finish coat in contemporary stucco work.

The composition of stucco depends on local custom and available materials. Stucco often contains substantial amounts of mud or clay, marble or brick dust, or even sawdust, and an array of additives ranging from animal blood or urine to eggs, keratin or glue size (animal hooves and horns), varnish, wheat paste, sugar, salt, sodium silicate, alum, tallow, linseed oil, beeswax, and wine, beer or rye whiskey. Waxes, fats, and oils were included to introduce water-repellent properties, sugary materials reduced the amount of water needed and slowed down the setting time, and alcohol acted as an air entrainer. All of these additives contribute to the strength and durability of the stucco.

The appearance of much stucco was determined by the color of the sand — or sometimes burnt clay — used in the mix. Often, stucco was also tinted with natural pigments, or the surface whitewashed or color-washed after stuccoing was completed. Brick dust could provide color, and other coloring materials that were not affected by lime, mostly mineral pigments, could be added to the mix for the final finish coat. Stucco was also marbled or marbleized — stained to look like stone by diluting oil of vitriol (sulfuric acid) with water, and mixing this with a yellow ochre, or another color. As the 20th century progressed, manufactured and synthetic pigments were added at the factory to some prepared stucco mixes.

Methods of Application

Stucco is applied directly, without lath, to masonry substrates, such as brick, stone, concrete, or hollow tile. But on wood structures, stucco, like its interior counterpart plaster, must be applied over lath in order to obtain an adequate key to hold the stucco. Thus, when applied over a log structure, stucco is laid on horizontal wood lath that has been nailed on vertical wood furring strips attached to the logs. If it is applied over a wood frame structure, stucco may be applied to wood or metal lath nailed directly to the wood frame; it may also be placed on lath that has been attached to furring strips. The furring strips are themselves laid over building paper covering the wood sheathing.

The dry materials must be mixed thoroughly before adding water to make the stucco.

|

Wood lath was gradually superseded by expanded metal lath introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When stuccoing over a stone or brick substrate, it was customary to cut back or rake out the mortar joints, if they were not already recessed, by natural weathering or erosion, and sometimes the bricks themselves were gouged to provide a key for the stucco. This helped provide the necessary bond for the stucco to remain attached to the masonry, much like the key provided by wood or metal lath on frame buildings.

Like interior wall plaster, stucco has traditionally been applied as a multiple-layer process, sometimes consisting of two coats, but more commonly as three. Whether applied directly to a masonry substrate or onto wood or metal lath, this consists of a first “scratch” or “pricking-up” coat, followed by a second scratch coat, sometimes referred to as a “floating” or “brown” coat, followed finally by the “finishing” coat. Up until the late 19th century, the first and the second coats were of much the same composition, generally consisting of lime or natural cement, sand, perhaps clay, and one or more of the additives previously mentioned. Straw or animal hair was usually added to the first coat as a binder. The third, or finishing coat, consisted primarily of a very fine mesh-grade of lime and sand, and sometimes pigment. As already noted, after the 1820s, natural cement was also a common ingredient in stucco, until it was replaced by Portland cement. Both masonry and wood lath must be kept wet or damp to ensure a good bond with the stucco. Wetting these materials helps to prevent them from pulling moisture out of the stucco too rapidly, which results in cracking, loss of bond, and generally poor-quality stucco work.

Traditional Stucco Finishes

Until the early 20th century when a variety of novelty finishes and textures were introduced, the last coat of stucco was commonly given a smooth, troweled finish, and then scored or lined in imitation of ashlar. The illusion of masonry joints was sometimes enhanced by a thin line of white lime putty, graphite, or some other pigment. Some 19th-century buildings feature a water table or raised foundation of roughcast stucco that differentiates it from the stucco surface above, which is smooth and scored. Other novelties and textured finishes associated with the “period” or revival styles of the early 20th century include the English cottage finish, adobe and Spanish, pebble-dashed or dry-dash surface, fan and sponge texture, reticulated and vermiculated, roughcast (or wet dash), and sgraffito.

Regular Maintenance

Although A.J. Downing alluded to stuccoed houses in Pennsylvania that had survived for over a century in relatively good condition, historic stucco is inherently not a particularly permanent or long-lasting building material. Regular maintenance is required to keep it in good condition. Unfortunately, many older and historic buildings are not always accorded this kind of care. An InterNACHI inspector can be consulted for advice regarding stucco maintenance.

Because building owners knew stucco to be protective, but also somewhat fragile coating, they employed a variety of means to prolong its usefulness. The most common treatment was to whitewash stucco, often annually. The lime in the whitewash offered protection and stability and helped to harden the stucco. Most importantly, it filled hairline cracks before they could develop into larger cracks and let in moisture. To improve water repellency, stucco buildings were also sometimes coated with paraffin, another type of wax, or other stucco-like coatings, such as oil mastics.

Assessing Damage

Most stucco deterioration is the result of water infiltration into the building’s structure, either through the roof, around chimneys, window and door openings, or excessive groundwater or moisture penetrating through or splashing up from the foundation. Potential causes of deterioration include ground settlement lintel and door frame settlement; inadequate and leaking gutters and downspouts; intrusive vegetation; moisture migration within walls due to interior condensation and humidity; vapor drive problems caused by the furnace, bathroom, and kitchen vents; and rising damp resulting from excessive groundwater and poor drainage around the foundation. Water infiltration will cause wood lath to rot, and metal lath and nails to rust, which eventually will cause stucco to lose its bond and pull away from its substrate.

The deteriorated surface of this catch basin is being re-stuccoed.

|

After the cause of deterioration has been identified, any necessary repairs to the building should be made first before repairing the stucco. Such work is likely to include repairs designed to keep excessive water away from the stucco, such as roof, gutter, downspout and flashing repairs, improving drainage, and redirecting rainwater runoff and splash-back away from the building. Horizontal areas, such as the tops of parapet walls and chimneys, are particularly vulnerable to water infiltration and may require modifications to their original design, such as the addition of flashing to correct the problem.

Previous repairs inexpertly carried out may have caused additional deterioration, particularly if executed in Portland cement, which tends to be very rigid and, therefore, incompatible with early, mostly soft lime-based stucco that is more flexible. Incompatible repairs, external vibration caused by traffic and construction, and building settlements can also result in cracks that permit the entrance of water and cause the stucco to fail.

Before beginning any stucco repair, an assessment of the stucco should be undertaken to determine the extent of the damage, and how much must be replaced or repaired. Testing should be carried out systematically on all elevations of the building to determine the overall condition of the stucco. Some areas in need of repair will be clearly evidenced by missing sections of stucco or stucco layers. Bulging or cracked areas are obvious places to begin. Unsound, punky, or soft areas that have lost their key will echo with a hollow sound when tapped gently with a wooden or acrylic hammer or mallet.

Identifying the Stucco Type

Analysis of the historic stucco will provide useful information on its primary ingredients and their proportions and will help to ensure that the new replacement stucco will duplicate the old in strength, composition, color, and texture as closely as possible. However, unless authentic, period restoration is required, it may not be worthwhile, nor in many instances even possible, to attempt to duplicate all of the ingredients (particularly some of the additives) in creating the new stucco mortar. Some items are no longer available, and others, notably sand and lime — the major components of traditional stucco — have changed radically over time. For example, most sand used in contemporary masonry work is manufactured sand, because river sand, which was used historically, is difficult to obtain today in many parts of the country. The physical and visual qualities of manufactured sand versus river sand are quite different, and this affects the way stucco works, as well as the way it looks. The same is true of lime, which is frequently replaced by gypsum in modern stucco mixes. And even if the identification of all the items in the historic stucco mix were possible, the analysis would still not reveal how the original stucco was mixed and applied.

There are, however, simple tests that can be carried out on a small piece of stucco to determine its basic makeup. A dilute solution of hydrochloric (muriatic) acid will dissolve lime-based stucco, but not Portland cement. Although the use of Portland cement became common after 1900, there are no precise cutoff dates, as stuccoing practices varied among individual plasterers, and from region to region. Some plasterers began using Portland cement in the 1880s, but others may have continued to favor lime stucco well into the early 20th century. While it is safe to assume that a late-18th or early-19th century stucco is lime-based, late-19th or early-20th century stucco may be based on either lime or Portland cement. Another important factor to take into consideration is that an early lime-stucco building is likely to have been repaired many times over the ensuing years, and it is probable that at least some of these patches consist of Portland cement.

Planning the Repair

Once the extent of damage has been determined, a number of repair options may be considered. Small hairline cracks usually are not serious and may be sealed with a thin slurry coat consisting of the finish coat ingredients, or even with a coat of paint or whitewash.

Commercially available caulking compounds are not suitable materials for patching hairline cracks. Because their consistency and texture is unlike that of stucco, they tend to weather differently, and attract more dirt; as a result, repairs made with caulking compounds may be highly visible and unsightly. Larger cracks will have to be cut out in preparation for more extensive repair. Most stucco repairs will require the skill and expertise of a professional plasterer.

The stucco will be applied to the wire lath laid over the area to be patched.

|

In the interest of saving or preserving as much as possible of the historic stucco, patching rather than wholesale replacement is preferable. When repairing heavily textured surfaces, it is not usually necessary to replace an entire wall section, since the textured finish, if well-executed, tends to conceal patches, and helps them to blend in with the existing stucco. However, because of the nature of smooth-finished stucco, patching a number of small areas scattered over one elevation may not be a successful repair approach unless the stucco has been previously painted, or is to be painted following the repair work. On unpainted stucco, such patches are hard to conceal, because they may not match exactly or blend in with the rest of the historic stucco surface. For this reason, it is recommended, if possible, that stucco repair be carried out in a contained or well-defined area, or if the stucco is scored, the repair patch should be “squared-off” in such a way as to follow existing scoring. In some cases, especially in a highly visible location, it may be preferable to re-stucco an entire wall section or feature. In this way, any differences between the patched area and the historic surface will not be so readily apparent.

The repair of historic stucco generally follows most of the same principles used in plaster repair. First, all deteriorated, severely cracked and loose stucco should be removed down to the lath (assuming that the lath is securely attached to the substrate), or down to the masonry if the stucco is directly applied to a masonry substrate. A clean surface is necessary to obtain a good bond between the stucco and the substrate. The areas to be patched should be cleaned of all debris with a bristle brush, and all plant growth, dirt, loose paint, oil, and grease should be removed. If necessary, brick or stone mortar joints should then be raked out to a depth of approximately 5/8-inches to ensure a good bond between the substrate and the new stucco.

To obtain a neat repair, the area to be patched should be squared-off with a butt joint using a cold chisel, a hatchet, a diamond blade saw, or a masonry bit. Sometimes, it may be preferable to leave the area to be patched in an irregular shape, which may result in a less conspicuous patch. Proper preparation of the area to be patched requires very sharp tools and extreme caution on the part of the plasterer not to break keys of surrounding good stucco by “over-sounding” when removing deteriorated stucco.

To ensure a firm bond, the new patch must not overlap the old stucco. If the stucco has lost its bond or key from wood lath, or the lath has deteriorated or come loose from the substrate, a decision must be made whether to try to re-attach the old lath, to replace deteriorated lath with new wood lath, or to leave the historic wood lath in place and supplement it with modern expanded metal lath. Unless authenticity is important, it is generally preferable (and easier) to nail new metal lath over the old wood lath to support the patch. Metal lath that is no longer securely fastened to the substrate may be removed and replaced in kind, or left in place and supplemented with a new wire lath.

When repairing lime-based stucco applied directly to masonry, the new stucco should be applied in the same manner, directly onto the stone or brick. The stucco will bond onto the masonry itself without the addition of lath because of the irregularities in the masonry or those of its mortar joints, or because its surface has been scratched, scored or otherwise roughened to provide an additional key. Cutting out the old stucco at a diagonal angle may also help secure the bond between the new and the old stucco. For the most part, it is not advisable to insert metal lath when re-stuccoing historic masonry in sound condition, as it can hasten deterioration of the repair work. Not only will attaching the lath damage the masonry, but the slightest moisture penetration can cause metal lath to rust. This will cause the metal to expand, eventually resulting in spalling of the stucco, and possibly the masonry substrate, too.

The final finish coat will be applied to this scratch coat.

|

If the area to be patched is properly cleaned and prepared, a bonding agent is usually not necessary. However, a bonding agent may be useful when repairing hairline cracks, or when dealing with substrates that do not offer a good bonding surface. These may include dense stone or brick, previously painted or stuccoed masonry, or spalling brick substrates. A good mechanical bond is always preferable to reliance on bonding agents. Bonding agents should not be used on a wall that is likely to remain damp or where large amounts of salt are present. Many bonding agents do not survive well under such conditions, and their use could jeopardize the longevity of the stucco repair.

A stucco mix compatible with the historic stucco should be selected after analyzing the existing stucco. It can be adapted from a standard traditional mix of the period, or based on one of the mixes included here. Stucco consisting mostly of Portland cement generally will not be physically compatible with the softer, more flexible, lime-rich historic stuccos used throughout the 18th and much of the 19th centuries. The differing expansion and contraction rates of lime stucco and Portland cement stucco will normally cause the stucco to crack. Choosing a stucco mix that is durable and compatible with the historic stucco on the building is likely to involve considerable trial and error, and probably will require a number of test samples, and even more, if it is necessary to match the color. It is best to let the stucco test samples weather as long as possible — ideally, one year, or at least through a change of seasons — in order to study the durability of the mix and its compatibility with the existing stucco, as well as the weathering of the tint, if the building will not be painted and color-match is an important factor.

If the test samples are not executed on the building, they should be placed next to the stucco remaining on the building to compare the color, texture, and composition of the samples with the original. The number and thickness of stucco coats used in the repair should also match the original.

After thoroughly dampening the masonry or wood lath, the first scratch coat should be applied to the masonry substrate, or wood or metal lath, in a thickness that corresponds to the original (if extant), or generally about 1/4-inch to 3/8-inch. The scratch coat should be scratched or crosshatched with a comb to provide a key to hold the second coat. It usually takes 24 to 72 hours, and longer in cold weather, for each coat to dry before the next coat can be applied. The second coat should be about the same thickness as the first, and the total thickness of the first two coats should generally not exceed about 5/8-inch. This second or leveling coat should be roughened using a wood float with a nail protruding to provide a key for the final or finish coat. The finish coat, about 1/4-inch thick, is applied after the previous coat has initially set. If this is not feasible, the base coat should be thoroughly dampened when the finished coat is applied later. The finish coat should be worked to match the texture of the original stucco.

Colors and Tints for Historic Stucco Repair

The new addition on the right is stucco scored to imitate the limestone of the historic building on the left.

|

The color of most early stucco was supplied by the aggregate included in the mix — usually, the sand. Sometimes, natural pigments were added to the mix, and 18th- and 19th-century scored stucco was often marbleized or painted in imitation of marble and granite. Stucco was also frequently coated with whitewash or a color wash. This tradition later evolved into the use of paint, its popularity depending on the vagaries of fashion, as much as a means of concealing repairs. Because most of the early colors were derived from nature, the resultant stucco tints tended to be mostly earth tones. This was true until the advent of brightly colored stucco in the early decades of the 20th century. This was the so-called “Jazz Plaster” developed by O.A. Malone, the “man who put color into California,” and who founded the California Stone Products Corporation in 1927. California Stucco was revolutionary for its time as the first stucco/plaster to contain colored pigment in its pre-packaged factory mix.

When patching or repairing a historic stucco surface known to have been tinted, it may be possible to determine through visual or microscopic analysis whether the source of the coloring is sand, cement, or pigment. Although some pigments or aggregates used traditionally may no longer be available, a sufficiently close color match can generally be approximated using sand, natural or mineral pigments, or a combination of these. Obtaining such a match will require testing and comparing the color of the dried test samples to the original. Successfully combining pigments in the dry stucco mix prepared for the finish coat requires considerable skill. The amount of pigment must be carefully measured for each batch of stucco. Overworking the mix can make the pigment separate from the lime. Changing the amount of water added to the mix, or using water to apply the tinted finish coat, will also affect the color of the stucco when it dries.

Generally, the color obtained by hand-mixing these ingredients will provide a sufficiently close match to cover an entire wall or an area distinct enough from the rest of the structure that the color differences will not be obvious. However, it may not work for small patches conspicuously located on a primary elevation, where color differences will be especially noticeable. In these instances, it may be necessary to conceal the repairs by painting the entire patched elevation, or even the whole building.

Many stucco buildings have been painted over the years and will require re-painting after the stucco repairs have been made. Limewash or cement-based paint, latex paint, or oil-based paint are appropriate coatings for stucco buildings. The most important factor to consider when repainting a previously painted or coated surface is that the new paint be compatible with any coating already on the surface. In preparation for re-painting, all loose and peeling paint, and other coating material not firmly adhered to the stucco, must be removed by hand-scraping or natural bristle brushes. The surface should then be cleaned.

Cement-based paints, most of which now contain some Portland cement and are really a type of limewash, have traditionally been used on stucco buildings. The ingredients were easily obtainable. Furthermore, the lime in such paints actually bonded or joined with the stucco and provided a very durable coating. In many regions, whitewash was applied annually during spring cleaning. Modern, commercially available, pre-mixed masonry and mineral-based paints may also be used on historic stucco buildings.

If the structure must be painted for the first time to conceal repairs, almost any of these coatings may be acceptable, depending on the situation. Latex paint, for example, maybe applied to slightly damp walls or where there is an excess of moisture, but latex paint will not stick to chalky or powdery areas. Oil-based or alkyd paints must be applied only to dry walls; new stucco must cure up to a year before it can be painted with oil-based paint.

Contemporary Stucco Products

There are many contemporary stucco products on the market today. Many of them are not compatible, either physically or visually, with historic stucco buildings. Such products should be considered for use only after consulting with a specialist in historic masonry. However, some of these pre-packaged tinted stucco coatings may be suitable for use on stucco buildings dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as long as the color and texture are appropriate for the period and style of the building. While some masonry contractors may, as a matter of course, suggest that a water-repellent coating be applied after repairing old stucco, in most cases, this should not be necessary, since color washes and paints serve the same purpose, and stucco itself is a protective coating.

Cleaning Historic Stucco Surfaces

Historic stucco buildings often exhibit multiple layers of paint or limewash. Although some stucco surfaces may be cleaned by water-washing, the relative success of this procedure depends on two factors: the surface texture of the stucco, and the type of dirt to be removed. If simply removing airborne dirt, smooth unpainted stucco, and heavily-textured painted stucco, may sometimes be cleaned using a low-pressure water wash, supplemented by scrubbing with soft natural bristle brushes, and possibly non-ionic detergents. Organic plant material, such as algae and mold, and metallic stains may be removed from stucco using poultices and appropriate solvents. Although these same methods may be employed to clean unpainted roughcast, pebble-dash, or any stucco surface featuring exposed aggregate, due to the surface irregularities, it may be difficult to remove dirt without also removing portions of the decorative textured surface. Difficulty in cleaning these surfaces may explain why so many of these textured surfaces have been painted.

When Total Replacement is Necessary

Complete replacement of the historic stucco with new stucco of either a traditional or modern mix will probably be necessary only in cases of extreme deterioration — that is, a loss of bond on over 40% to 50% of the stucco surface. Another reason for total removal might be that the physical and visual integrity of the historic stucco has been so compromised by prior incompatible and ill-conceived repairs that patching would not be successful.

When stucco no longer exists on a building, there is more flexibility in choosing a suitable mix for the replacement. Since compatibility of old and new stucco will not be an issue, the most important factors to consider are durability, color, texture and finish. Depending on the construction and substrate of the building, in some instances, it may be acceptable to use a relatively strong cement-based stucco mortar. This is certainly true for many late 19th and early 20th century buildings, and may even be appropriate to use on some stone substrates, even if the original mortar would have been weaker, as long as the historic visual qualities noted above have been replicated. Generally, the best principle to follow for a masonry building is that the stucco mix, whether for repair or replacement of historic stucco, should be somewhat weaker than the masonry to which it is to be applied in order not to damage the substrate.

General Guidance for Historic Stucco Repair

A skilled professional plasterer will be familiar with the properties of materials involved in stucco repair and will be able to avoid some of the pitfalls that would hinder someone less experienced. General suggestions for successful stucco repair parallel those involving restoration and repair of historic mortar and plaster. In addition, the following principles are important to remember:

- Mix only as much stucco as can be used in one-and-a-half to two hours. This will depend on the weather (mortar will harden faster under hot and dry, or sunny conditions). Experience is likely to be the best guidance. Any remaining mortar should be discarded; it should not be re-tempered.

- Stucco mortar should not be over-mixed. (Hand mix it for 10 to 15 minutes after adding water, or machine-mix for three to four minutes after all ingredients are in mixer.) Over-mixing can cause crazing and discoloration, especially in tinted mortars. Over-mixing will also tend to make the mortar set too fast, which will result in cracking and poor bonding or keying to the lath or masonry substrate.

- Wood lath or a masonry substrate, but not metal lath, must be thoroughly wetted before applying stucco patches so that it does not draw moisture out of the stucco too rapidly. To a certain extent, bonding agents also serve this same purpose. Wetting the substrate helps retard drying.

- To prevent cracking, it is imperative that stucco not dry too fast. Therefore, the area to be stuccoed should be shaded, or even covered, if possible, particularly in hot weather. It is also a good idea in hot weather to keep the newly stuccoed area damp, at approximately 90% humidity, for a period of 48 to 72 hours.

- Stucco repairs, like most other exterior masonry work, should not be undertaken in cold weather (below 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and preferably warmer), or if there is a danger of frost.

Historic Stucco Textures

Most of the oldest stucco in the U.S. dating prior to the late 19th century will generally have a smooth, troweled finish (sometimes called a “sand” or “float” finish), possibly scored to resemble ashlar masonry units. Scoring may be incised to simulate masonry joints, the scored lines may be emphasized by black or white penciling, or the lines may simply be drawn or painted on the surface of the stucco. In some regions, at least as early as the first decades of the 19th century, it was not uncommon to use a roughcast finish on the foundation or base of an otherwise smooth-surfaced building. Roughcast was also used as an overall stucco finish for some outbuildings and other less-important types of structures.

This stucco house has a roughcast finish.

|

A wide variety of decorative surface textures may be found on revival style stucco buildings, particularly residential architecture. These styles evolved in the late 19th century and peaked in popularity in the early decades of the 20th century. Frank Lloyd Wright favored a smooth finish stucco, which was imitated on much of the Prairie style architecture inspired by his work. Some of the more picturesque surface textures include English Cottage or English Cotswold finish; sponge finish; fan texture; adobe finish; and Spanish or Italian finish. Many of these finishes and countless other regional and personalized variations on them are still in use.

The most common early 20th-century stucco finishes are often found on bungalow-style houses and include: spatter or spatter dash (sometimes called roughcast, harling, or wet dash), and pebble-dash or dry dash. The spatter dash finish is applied by throwing the stucco mortar against the wall using a whisk broom or a stiff fiber brush, and it requires considerable skill on the part of the plasterer to achieve a consistently rough wall surface. The mortar used to obtain this texture is usually composed simply of regular sand, lime, and cement mortar, although it may sometimes contain small pebbles or crushed stone aggregate, which replaces half the normal sand content. The pebble-dash or dry dash finish is accomplished manually by the plasterer throwing or “dashing” dry pebbles (about 1/8-inch to 1/4-inch in size)onto a coat of stucco freshly applied by another plasterer. The pebbles must be thrown at the wall with a scoop with sufficient force and skill that they will stick to the stuccoed wall. A more even or uniform surface can be achieved by patting the stones down with a wooden float. This finish may also be created using a texturing machine.

Stucco on historic buildings is especially vulnerable not only to the wear of time and exposure to the elements but also at the hands of well-intentioned “restorers” who may want to remove stucco from 18th and 19th-century structures to expose what they believe to be the original or more “historic” brick, stone or log underneath. Historic stucco is a character-defining feature and should be considered an important historic building material, significant in its own right. While many 18th and 19th century buildings were stuccoed at the time of construction, others were stuccoed later for reasons of fashion or practicality. As such, it is likely that this stucco has acquired significance, over time, as part of the history and evolution of a building. Thus, even later, non-historic stucco should be retained, in most instances; and similar logic dictates that new stucco should not be applied to a historic building that was not stuccoed previously. When repairing historic stucco, the new stucco should duplicate the old as closely as possible in strength, composition, color, and texture.

This article was sourced from the United States National Park Service

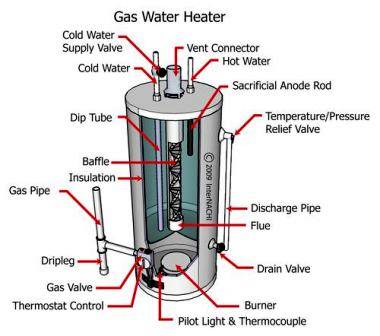

Construction Quality of the Water Heater

Construction Quality of the Water Heater

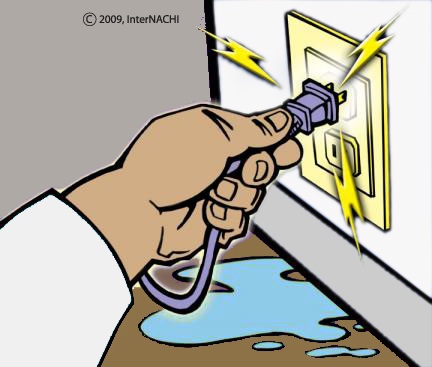

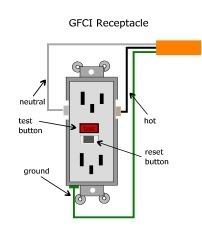

GFCIs are designed to provide protection in such a situation, unlike standard circuit breakers, which guard against overloads, short circuits and ground faults.

GFCIs are designed to provide protection in such a situation, unlike standard circuit breakers, which guard against overloads, short circuits and ground faults. re they are working properly and are providing protection from fatal shock.

re they are working properly and are providing protection from fatal shock.